Projet Sape // Publication in African Cities Reader 1 // 2009

Publié en 2009 dans African Cities Reader 1 // Chimurenga and African Centre for Cities // Capetown.

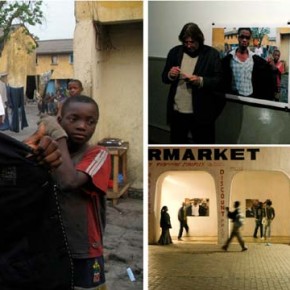

Le principe de cette publication – projet est de montrer simultanément la photo et le lieu où elle a été exposée, principalement dans les espaces urbains de Kinshasa et Johannesburg.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The principle of this publication – project is to show simultaneously the picture and the place where she was exhibited, mainly in urban spaces in Kinshasa and Johannesburg.

Avec : The Smarteez, Dorothée Kreutzfeldt, Athi Patra Ruga, Lolo Veleko, performant les images à Johannesburg.

SHOUT-OUT … The sapeurs in the pictures/Les sapeurs dans les photos :

Dicoco Boketshu, Djanga Weni, Sankhara, Petit Yannick, Vieux Dauda, Bebeto, Gervais Mavinga, Tresor Omeyaka (Python), Olivier Lunama (Boston, L’Homme à Rayon), Johnny Efoloko, Bijou Diama (Vrai Djo), Trésor Tombi (Yohji), Guelord Kanza (Japon), Arnaud Madienga (Double Impact), Chris Setchi, Franck Ngoy Nzumbi (Youssou N’Dour), Eric Bokeke (Kenzo), Christian Tangui (Le Bourgeois), Christian Wanani (Firenze), Blaise Tayaya (Peter Kokopy), Sacré Lubamba (Yodji), Gantine et Ses Actrices, Dédé Forme (Toutankhamon), Kebere Mbondos, Foumadj, Itchay Bessongo, Patou Koucha (Grand Père), Alain Mouela (Van Deutsch), Les musiciens de Johnny Loko…

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

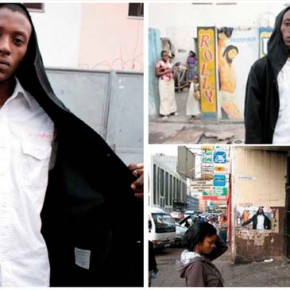

I have been working in Kinshasa, DRC since 2001. Early on, there, I encountered sape. There are many ways to describe sape. Few, however, can effectively capture its intense complexity and none can claim to « explain » it. It is far too rich and shifting a phenomenon for such. Broadly, then – and of necessity too broadly – a definition: what I speak of here is a set of practices involving young men and women that revolves around intersections between street fashion, haute couture, performance and « dressing up ». Sape is the art of dressing to kill.

Initially, sape had me stumped: why was it, I asked myself, that people who have exceedingly little chose to forego food in order to acquire and appear in public in costly designer clothes? Wherefore this fascination – this obsession, it seemed to me – with elegance? To what ends the competitions I witnessed between crews of sapeurs (this the name that adepts of the practice give themselves)? How does this all work, for sape is more than clothes worn and displayed; it is also clothes exchanged, bought, sold, smuggled and (sometimes) copied: a vast economy, monetary of course, but also implicitly political, social, symbolic and emotionally deeply fraught. In an attempt to gain a foothold in the face of all these questions I began looking, asking, documenting.

In 2006, PROGR, a contemporary art centre in Bern, Switzerland, asked me to develop an exhibition. Out of conversations back and forth was born the idea of a scenography (scenography is my ambit; I am not a photographer): a series of photo shoots that would be face-to-face encounters. Sapeurs would pose, taking on with their gaze the lens of my camera, talking (back) to an audience yet to be – people who, in time, would see the photos developed and blown up. The plan was for the photos to be shown in Mikili. Mikili is a place. The name comes from the Lingala word mokili, meaning « the world ». In Kinshasa, it refers to Europe, to – so they say in DRC – the « clean countries », those one hopes to travel to because life there seems as if it might be better than « back home ».

The photo shoots were a stunning mix of moments: dance moves; poses inspired by fashion magazines; mirror-mirror-on-the-wall games (imitation, parody, flashes of humour, of irony) played (out) with mundele (white folks); grotesques… At the heart of it all, ebbing and flowing, were fragments of a body language, highly fluid and varied, shared across vast swaths of Kinshasa. That and a great deal of sadness, too: in the gaze, again, in gazes that, at given moments, chose emphatically not to engage.

The images born of this process are the product of a doube exchange. They speak to and they speak from the context in which they came to life: the street that is the locus of each shoot and the people on the street who witness(ed) the shoot. For sape is a spectacle in Kinshasa and so each photo session turned into a party attended by many guests. In the photos themselves, the bodies of the sapeurs, their clothes, presented by the wearers so that labels can be clearly read (Yves St Laurent, Gucci, Versace, Yamamoto), upstage the city, hiding (or, in any event, rendering it less immediately visible) this city which many sapeurs claim is « dirty » (« You want to know why we sape? I was told over and over again; “to stay clean (pour rester propre) ») – this city that so many sapeurs say they want to leave.

The photos, once shot, were developed, blown up close to life size (persons shown in the shots stand at a little over 1m65) and shown in and around the streets where they were taken.

Since 2006, on every one of my trips to DRC, I organize and film sape meets. Most are with men, but women feature as well. Without the assistance of trusted Kinois friends, these sessions would not be possible. From the very beginning, these friends too have been documenting the sape phenomenon and producing a body of photographic images about it. In the first photo exhibit of the sape project held outside DRC – in Bern – their photos and mine appeared alongside one another. At the centre of it all – fundamental to the entirety of this project – are the guidance, gaze and generosity of Dicoco Boketshu, a musician, video and performance artist based in Kin, and Djanga Weni, also a musician (both men are members of Trionyx, a band founded by Kinois composer, performer and educator Bebson de la Rue). Also key to the undertaking are artists Androa Mindre, Freddy Mutombo and Kens Mukendi.

Sharing – conviviality – is an integral part of the project. When in Kin, as a group, Dicoco, Djanga, Androa, Freddy, Kens and I spend hours over beer and chunks of grilled meat discussing issues, styles, approaches. These comings together are essential: they make it possible for me to avoid – or, at any rate, help me keep at bay – an outsider’s gaze; they allow me to get into and to grapple with the complex skein of things. These moments when we link up are intense, rich in joy and camaraderie.

Each shoot poses a set of fundamental questions. Exchange is one. Means (of which I have few) must be found to do one, essential thing: develop the photos relatively quickly to show them to those whom they depict and, where possible, leave prints with them. I say that this is essential for a simple but sad reason: foreigners are constantly coming to Kin, photographing and going home, leaving nothing behind. What images Kinois do see of themselves, their city and the lives they live there – typically in the press and on TV – make little sense to them. They are largely negative images, images that sensationalize what the photographers represent as unadulterated misery, images that say little or nothing of actual lives lived. In reaction to this ever-so-common practice, some of the Kinois friends with whom I work have developed rich practices aimed at self-representation – at showing Kin through Kinois eyes. Thus Kens Mukendi’s photographs, which document sape competitions, and a series of images by Dicoco Boketshu which go beyond documentation into full-fledged of mise-en-scène: the staging of elegant, imaginary scenes that give tangible form to fictions – to dreams – of Mikili.

I try to ensure that each sapeur with whom I work receives a small salary as well as a print of a photograph in which he appears. Oftentimes, after the fact, one finds the image in his home, framed or taped to a wall. We shoot video as well and organize showings in the city: on the street; in places where the photos were shot; at sapeurs’ houses; once, even, in a police barracks. Each presentation turns into a party, rich in narcissistic pride. Places I thought I would never be able to enter open up to me; thanks to this ongoing process I am able to go deeper into this otherwise guarded city.

In Bern, the photos were shown in a gallery (nothing on the streets, I was told: « the images are too tough… »). Clearly, a white cube is not where they belong, however; in a traditional « Northern » exhibition space, the object – the image – overshadows the process, the relationships and the exchanges that are at its heart. These are works that need to be shown in public spaces. They call for the street. And so my friends and I decided to show them, maxi-sized, on the streets of Kinshasa, during an event entitled Urban Scenographies (an ongoing, multi-city series of artists’ residencies held across the world as the result of collaborations between ScU2, a collective I run with my friend and colleague François Duconseille, and artists’ collectives based in Douala, Cameroon (Cercle Kapsiki) Alexandria, Egypt (Gudran), Kinshsasa (Eza Possibles) and, since then (and most recently) Johannesburg, with JPP) (http://www.eternalnetwork.org/scenographiesurbaines).

When work first began on the project, the notion had been to tape the images on façades, billboards and such in Paris, Brussels and Tokyo (sapeurs commonly refer to themselves as « Japanese citizens » because they hold in particularly high esteem haute couture by the likes of Yoshhi Yamamoto and Issey Miyake). The idea was to create a face-to-face exchange, so that the photos, via their presence, might interrogate these « high end » urban spaces where the clothes that sapeurs sport are originally sold. I do not know if this particular iteration of the project will come to pass; time will tell. One thing is certain, though: this type of approach, if implemented, will have to be confrontational – a provocation of sorts. For it seems fairly clear that these images – of Kinois sapeurs in effect high-jacking the high-luxe of places that think so well of themselves – are not images that these places are particularly keen to showcase. In France, the reactions I have met are often problematic: people like what they see because they think that what they are looking at are grunge fashions shots, cool because funky and/or trashy … not a « take » I find interesting or have too much patience with. Then again, I suppose, I must take into account the fact that different people will see the photos in different ways depending on where they encounter them.

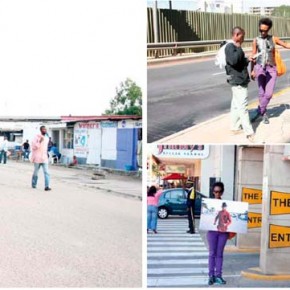

I was still grappling with the French responses when I received an invitation to show the photographs in Johannesburg, in the context of a residency sponsored by the Joubert Park Project (JPP) and IFAS (French Institute/South Africa). I agreed and a project developed in partnership with artists Athi Patra Ruga and Dorothy Kreutzfeldt. We decided to tape up life-sized blow-ups of the images in and around the Drill Hall, in the CBD, in Yeoville, where many folks hailing from DRC live, and in Rosebank, at the hippest mall in town, The Zone. The plan was for a distinctively performative event.

Things got rolling fast. Photographer Lolo Veleko introduced me to the Smarteez, a group of young artists cum fashionistas whom she works with in Soweto. Together, we taped images on buildings, billboards, fences and other outdoor spaces. Some stayed up for weeks, others were torn down in a matter of hours. Just about everybody in the CBD and in Yeoville got it: here, there didn’t seem to be a disconnect a « what the hell is this? » factor. Sape made sense. Conversations got started, exchanges, questions…

In Rosebank, the situation was a little more complicated. It proved impossible to tape up the images anywhere in the Zone. The whole place is under 24 hour surveillance – security men and CCTV. Also – and clearly this is intentional: part of the place’s look – there are no flat, free or blank spaces onto which the images could be affixed. So, with Athi Patra Ruga, we organized a march: the Smarteez and friends bore the images aloft, like placards. Wherever we sensed a crack in the disciplinarian structure of the location, we gave it a shot: propped up an image against a wall, set it up in a shop window. It was an easy, casual march – more of a stroll, really – but it got us in trouble nonetheless. We were shown out by security. We made our way into the parking area surrounding the mall. This worked nicely, but was not quite the disappearing act that security had had in mind for us… To get into the Zone, you must first park, so the images were the first thing people coming in saw and, icing on the cake for our move, the overwhelming majority of the car-park guards at The Zone are Congolese.

As we walked among the cars, joshing with the Congolese guards, it felt as if the sapeurs in the images were among us, moving with us. At the same time, the fact that they were there in image and not in the flesh underscored the fact that they could not – that they cannot – move, that it was physically impossible for them to be with us lelo awa, as Kinshasa artist Méga Mingiendi might put it : « here, now, today. » This place, where the fashion they sport is so « in », is « out » for the sapeurs whose presence and absence both haunted our performance. This – this presence/absence and this haunting – everyone saw and called out right away when, back in Kin, I showed footage of the Rosebank march. It was part and parcel of the moment in both cities.

As the end of the Joburg residency, we organized a « fashion event » in the street in front of the Drill Hall. We called the event « 100th Year Wear » – a word play on « 100 Years War », this the name of a sapeur crew in Kinshasa (« Guerre de 100 Ans »). (There are many different crews, a number of which use allusions to war in their names; a case in point is « Guerre Sans Fin »- « Never-Ending War ».) The event was meant to juxtapose fashionista moves and practices in Jozi to Kin moves and practices as seen in video and photo images of sapeurs shot in DRC. What we were interested in foregrounding were the politics of sape : the body politics of it. What we were after was an understanding (or a glimpse) of ways in which individual identities are constructed and expressed through performative uses of the body as moving flesh, clothed entity and concept(s) embodied. In the process, intersections – meetings of form, ideas, words, movements – emerged that brought to the fore a notion that is coming to play a increasingly powerful role worldwide : MY BODY IS MY COUNTRY.

Interested? Stay tuned…

Jean-Christophe Lanquetin

Translation: Dominique Malaquais

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

VERSION FRANÇAISE :

Je travaille depuis 2001 à Kinshasa, en tant que scénographe. Au départ, l’omniprésence et la force du phénomène de la sape à Kinshasa est pour moi une énigme : pourquoi des gens se sapent t’il avec des habits griffés et chers alors qu’ils ont à peine de quoi manger ? Pourquoi cette fascination, cette obsession me semble t’il, de l’élégance, pourquoi ce système d’échanges, ces concours que je découvre dans la rue, concours entre bandes de sapeurs ?

J’observais, j’assistais, je posais des questions, je documentais.

En 2006, le PROGR, un centre d’art contemporain à Berne (Suisse), me commande un projet pour une exposition à Berne. Vient l’idée d’un dispositif scénographique (je ne suis pas photographe), un face à face dont la photo serait le medium : les sapeurs posent, regardent l’objectif, adressent quelque chose aux spectateurs. Je leur explique que les photos seront montrées à « mikili », de « mokili », le monde en Lingala, en fait ici surtout l’Europe, les pays « propres » (disent-ils), où l’on rêve de voyager parce que la vie y semble meilleure.

Postures de danse, positions inspirées de revues de modes, jeux de miroirs (imitation, parodie, instantanés ludiques) avec les « mundele » (les blancs en lingala), grotesques. Des fragments de cette culture gestuelle commune aux kinois, en constante évolution, émergent.

Mais aussi beaucoup de tristesse dans les regards, des évitements.

Adresse donc, mais dans le contexte urbain : les images sont construites dans une double relation, d’adresse et de présence du contexte, la rue et les spectateurs de la séance de prise de vue. Car la sape est un spectacle en soi, à Kinshasa, et chaque séance devient une fête, attirant un large public.

Sur les photos, le corps des sapeurs, leurs vêtements ouverts, leurs poses, cachent la ville, cette ville « sale » (disent-ils encore : « c’est pour rester propre » qu’on se sape, me dit-on encore et encore), cette ville qu’ils rêvent de quitter.

Les images sont exposées en grand format, la taille du corps photographié proche du corps spectateur. Le niveau de l’œil est 1,65m. De façon à faire exister le face à face dans l’espace.

Ainsi, depuis 2006, à chaque séjour, nous organisons des séances de sape avec des groupes d’hommes mais aussi de femmes, aidé par les amis kinois avec qui j’ai une relation de confiance. Ils les rendent possibles. Eux aussi se mettent à documenter, à photographier. Dès le projet à Berne, j’expose leur travail en parallèle du mien. Fondamental à ce projet, l’aide, le regard, le partage avec Dicoco Bokhetsu – musicien, vidéaste, performer- et Djanga Weni, musicien lui aussi (tous deux sont membres de Trionyx, groupe fondé par Bebson de la Rue) ; Androa Mindre Kolo, Freddy Mutombo, Kens Mukendi, artistes.

La convivialité fait partie du processus. Nous discutons longuement, mangeons, buvons, ces discussions sont essentielles, elles permettent de ne pas travailler d’en dehors, de rentrer dans la complexité des choses. L’intensité, la générosité, le plaisir sont ici importants.

Avec chaque séance se pose la question de l’échange (j’ai peu d’argent). Montrer les images à Kinshasa et en donner aux sapeurs s’avère essentiel. Car il y a cette pratique récurrente de la part des étrangers, de prendre des photos et de partir avec. Les kinois voient pour l’essentiel des images, de leur ville, de leur vie, sur les écrans tv, dans les journaux. Ils ne se reconnaissent pas dans la manière très souvent négative, voire misérabiliste, dont on parle d’eux, dont on montre leur vie. D’où une méfiance, compréhensible. D’où le choix, aussi, de faire des images, de se dire soi même : ainsi les photos de Kens Mukendi documentant un concours, et celles prises par Dicoco Bokhetsu qui vont au delà de la documentation pour mettre en scène imaginaires, fictions, rêves de l’ailleurs « mikili ».

Outre un petit salaire, j’essaye de faire en sorte que chaque sapeur reçoive une image ; souvent on retrouve celle-ci accrochée chez lui. Des présentations vidéo ont lieu à Kinshasa, dans la rue, sur les lieux où ont été prises les photos, chez les bandes de sapeurs, dans un camp de la police… Chaque fois c’est la fête, avec aussi des effets narcissiques. Des endroits que je pensais impossibles d’accès s’ouvrent, je peux circuler plus en profondeur dans cette ville difficile d’accès.

A Berne, les images sont montrées dans une galerie (on refuse l’exposition dans la rue, trop dures, les photos, me dit-on). Mais d’évidence ce n’est pas leur place (l’objet photographique prend le pas sur le dispositif relationnel). C’est l’espace public, la rue, qui s’impose.

Nous les exposons en grand format dans la rue à Kinshasa pendant les Scénographies Urbaines (note sur les scéno urbaines).

L’idée initiale est de coller les images dans la rue, aussi à Paris, Bruxelles, Tokyo (les sapeurs de déclarent tous « japonais », la mode japonaise – Yamamoto, Miyake…- étant particulièrement prisée), pour fabriquer un face à face, afin que les photos interrogent par leur présence dans les lieux de luxe d’où viennent les habits portés par les sapeurs. Je ne suis pas sûr d’y parvenir un jour, sauf sous forme de performance provocatrice, tant je pressens que l’on a pas envie de les voir dans de tels lieux. Quelques personnes, en France, qui connaissent le milieu de la mode, voient les images comme des photos de mode trash. Bon… Je me rends compte que leur sens varie beaucoup en fonction de l’endroit d’où on les voit.

On me propose de les exposer à Johannesburg, (lors d’une résidence à l’invitation de l’Institut Français et de The Joubert Park Project). Le dispositif se met en place avec Athi Patra Ruga et Dorothée Kreutzfeldt, artistes. Il s’agit de coller les images dans la rue, dans différents endroits de Johannesburg, le fashion district, autour du Drill Hall (dans le CBD), à Yeoville (où vit la communauté congolaise), et à Rosebank (« the Zone », le centre commercial le plus branché). L’effet attendu : que ces séances aient une dimension performative.

Lolo Veleko, photographe, me fait rencontrer les Smarteez, de jeunes artistes et fashionistas de Soweto avec qui elle travaille. Nous collons les photos ensemble. Une « chaine » s’esquisse. Certaines photos restent pendant des semaines, d’autres sont arrachées presque tout de suite. Les gens, dans la rue, captent instantanément ce dont il s’agit, la culture de la sape semble assez universellement partagée. Discussions, échanges, questions…

A Rosebank, impossible de coller les images : « the Zone », le centre commercial, est sous contrôle, caméras de surveillance et vigiles. De plus, il n’y a pas de surfaces libres – but recherché, d’ailleurs. Alors, avec Athi Patra Ruga, nous organisons une marche, les Smarteez et quelques complices portent les images. Nous les mettons en situation, dans la rue, dans les allées, dans les vitrines… Cette simple marche avec les photos, balade presque, déclenche la réaction des vigiles, ils nous indiquent la sortie. Nous nous dirigeons vers les parkings ; la balade continue. Ce n’est pas ce qu’espéraient les vigiles, car les parkings sont partie intégrante de la Zone, et, qui plus est sont gardés par des Congolais.

Les sapeurs kinois sont comme « parmi nous », leur présence en images renvoie à l’impossibilité physique de leur présence « ici, maintenant, aujourd’hui », « lelo awa , dirait l’artiste Mega Mingiedi. Lorsque je montre à Kinshasa cette marche à Rosebank, tout le monde comprend immédiatement la portée de ce moment.

Pour clore la résidence, nous organisons un « fashion event » au Drill Hall, dans la rue. Cela s’appelle « 100th Year Wear ». (de « Guerre de 100 ans, » le nom d’un des groupes de sapeurs à Kin – il y a aussi « Guerre sans fin », etc…). Son principe est de juxtaposer des pratiques fashionistas à Johannesburg avec les photos et films des sapeurs kinois. C’est la dimension politique de la sape qui ici nous intéresse : « body politics ». La manière dont des identités individuelles se construisent et s’expriment à partir des pratiques du corps et du vêtement. Les juxtapositions renvoient à une idée qui me semble de plus en plus prégnante : « mon corps est mon pays ».

A suivre.

JcLanquetin

SHOUT-OUT … The sapeurs in the pictures/Les sapeurs dans les photos :

Dicoco Boketshu, Djanga Weni, Sankhara, Petit Yannick, Vieux Dauda, Bebeto, Gervais Mavinga, Tresor Omeyaka (Python), Olivier Lunama (Boston, L’Homme à Rayon), Johnny Efoloko, Bijou Diama (Vrai Djo), Trésor Tombi (Yohji), Guelord Kanza (Japon), Arnaud Madienga (Double Impact), Chris Setchi, Franck Ngoy Nzumbi (Youssou N’Dour), Eric Bokeke (Kenzo), Christian Tangui (Le Bourgeois), Christian Wanani (Firenze), Blaise Tayaya (Peter Kokopy), Sacré Lubamba (Yodji), Gantine et Ses Actrices, Dédé Forme (Toutankhamon), Kebere Mbondos, Foumadj, Itchay Bessongo, Patou Koucha (Grand Père), Alain Mouela (Van Deutsch), Les musiciens de Johnny Loko…